Bush lost because voters punished him for the recession of the early 1990s - an event he did not cause. This is just one example of a broader phenomenon of voters rewarding and punishing politicians for things they do not control.

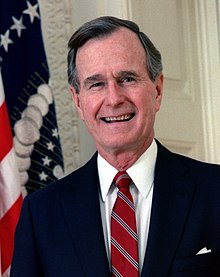

President George H.W. Bush, whose funeral is today, is now a much-admired figure on both sides of the political spectrum. But it wasn't always so. Although he achieved high approval ratings early in his administration, his popularity plummeted, and he suffered a painful defeat in his 1992 reelection bid.

Why did that happen? Pollsters and other experts overwhelmingly agree , as the Bill Clinton campaign famously put it, that it was "the economy, stupid." Voters punished Bush for the recession of the early 1990s, which came at exactly the right time to doom Bush's reelection prospects. Had it come a year earlier or a few years later, Bush would likely have won.

Dumping Bush because of the recession might have made sense if he and his policies had caused it. But few if any economists believe that to be the case. Rather, experts generally conclude that the cause was some combination of business cycle effects and trends in financial markets. Ultimately, Bush lost primarily because economically ignorant voters blamed him for an event he did not cause.

The 1992 election was not an isolated historical curiosity. Studies find that voters in both the United States and around the world routinely reward and punish incumbent politicians for events they have little or no control over, while often ignoring more subtle policy effects that the incumbents really are responsible for. Short-term trends in the economy are the most ubiquitous example. But they are far from the only one. Voters also reward and punish incumbents for such events as droughts, shark attacks, and even local sports team victories.

The point here is not that the voters were necessarily wrong to reject Bush (or any other particular politician). In 1992, there were perfectly plausible reasons to believe that Bill Clinton, sex scandals notwithstanding, would be a better president than Bush. The real cause for concern is that in this case - and many others - voters were deciding based on flawed criteria. That greatly increases the risk of error. Using such criteria might still lead to a good outcome. Sometimes, people can make the right decision for the wrong reasons. But when that happens, it is largely a matter of luck.

The problem is not just that ignorance might cause the electorate to choose the "wrong" candidate out of those who get nominated by the major parties. It is also that it reduces the quality of the choices available to us in the first place. Knowing that they face a largely ignorant electorate, candidates and parties adopt platforms and campaign strategies that cater to that ignorance. In that respect, public ignorance helps ensure that we are all losers long before election day.

Rewarding and punishing politicians for short-term economic trends is an example of "retrospective voting" - making electoral decisions based on simple metrics of whether things seem to be going well or badly under the rule of the incumbent. Most voters know little about government and public policy, in large part because it is rational for them to devote little or no time to learning such information. As a result, they tend to rely on crude "information shortcuts" to make decisions, of which retrospective voting is one of the most commonly used. Unfortunately, such shortcuts are often unreliable, in part because their effective use can require knowledge that generally ignorant voters do not possess (in this case, knowledge of what outcomes incumbents really are responsible for).

There is no easy solution to the kind of public ignorance that doomed Bush in 1992 and impacts many other elections, as well. But we should at least be more aware of the problem, and recognize that it is a systemic flaw, not one limited to a particular election, or to voters on one side of the partisan divide.

In my own work on political ignorance, I argue that the most promising approach is limiting and decentralizing government power, thereby increasing opportunities for people to "vote with their feet," in which framework they have much stronger incentives to become well-informed than when making choices at the ballot box. But there are also other options worth considering, such as voter education initiatives, "sortition," and directly incentivizing citizens to increase their knowledge. As we remember George H.W. Bush and consider his legacy, we should also keep in mind the problem highlighted by his defeat in 1992, and begin to take it more seriously.

No comments:

Post a Comment